Vaseline Glass – The Magic of the Arc Light

Based on our research and first published in our NetworK ezine in January 2018.

|

Vaseline Carnival Glass is generally understood to have a yellow-green base glass that reacts vividly under UV (black light) giving a transparent, vivid, yellow-green, fluorescent glow.

The reason for the glow is that the glass batch contains uranium dioxide as a colorant, and when exposed to ultra-violet light, the electrons in the glass are “excited” which causes that magical glow (known as fluorescence). Uranium dioxide is believed to have been first used as a colorant for glass in the mid-1800s, and it was extensively used by glass makers all over the world until WW2 (its use began again later, but that’s a story for another day). Today’s collectors adore Vaseline (also called uranium glass) for its trickery and magic … we love the way it lights up like crazy when we shine our black lights on it! |

Above: a group of vaseline (uranium) Carnival Glass under a UV black light.

|

What made Vaseline glass so popular, back in the late 1800s and the early 1900s?

|

There’s a general feeling that it was because Vaseline has a gentle glow when the rays of the sun touch it. Place it in a window and watch the subtle hint of a glow, a kind of luminescence – it’s especially interesting at dusk when there’s less visible light and so the UV rays of the setting sun get more chance to make the glass fluoresce. So, was it that hint of a glow in the setting sun that made people go crazy for Vaseline? Certainly, that was a delightful effect and was surely enjoyed by many, but it wasn’t anything like the razzmatazz WOW effect a black (UV) light produces. But of course, it’s only today’s collectors that have such a thing as a UV light. Right? Well actually, no it’s not. Back in the late 1800s and the early 1900s, they knew all about that crazy, vivid UV fluorescence that you get with Vaseline glass, because they had their own version of UV black lights! And it was almost certainly a big selling point for Vaseline glass. |

Two amazing comports in Vaseline Carnival - Fenton's Peacock and Urn (left)

and Millersburg's Acorn. Pictures courtesy of Seeck Auctions. |

|

How do we know all this?

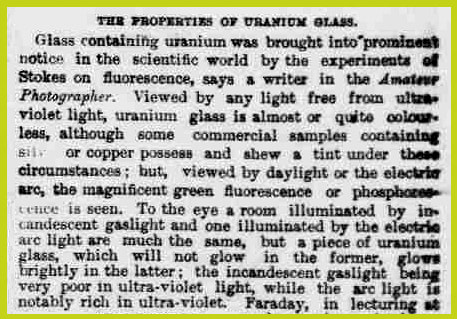

Well, we have solid, actual proof in the form of a contemporary report from 1897 that appeared in a British newspaper. As clearly explained in the report, the popularity of Vaseline glass was undoubtedly due to the fascinating effects it produced in certain kinds of light – and that crazy UV glow was well understood by the Victorians, thanks to the scientific experiments on fluorescence by George Stokes and others (in fact Stokes had coined the term “fluorescence” in 1852, to describe how uranium glass changes under different light conditions). Here’s the proof we found: on the right is the 1897 newspaper article (which was about uranium glass). It explained how the vivid glow showed brightly under UV light, saying that, when viewed by any light free from UV light, uranium glass is colourless … but viewed by daylight or the electric arc light (rich in UV) the magnificent green fluorescence is seen. If only we could travel back in time, we’d be able to understand so much more. But the next best thing is to read what people actually reported in the past – and that’s why old newspaper reports like this one are so important. |

|

It was all down to the Electric Arc Lamp!

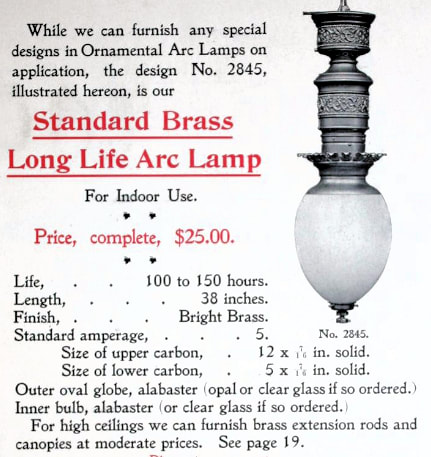

The astonishing eye witness account from 1897 tells us that when uranium glass (Vaseline) was looked at in the light from an electric arc lamp, the amazing, vivid green fluorescence could be seen. The electric Arc Lamp was the very first kind of commercially successful electric light. They emitted a super-bright purplish-white light, which was in fact UV light. When Vaseline glass was viewed under an arc lamp, emitting UV light, it would have glowed crazy bright green – it must have looked like magic! Back in the 1800s and into the early years of the 1900s, they actually had their own version of black lights that made Vaseline glass glow. By 1890 there were more than 130,000 arc lamps in use in the

United States alone. By 1900 there were around half a million. |

An 1897 ad for a Bergmann arc lamp for indoor use.

|

Arc lights were mainly used to illuminate large areas – factories, hotels, exhibition areas and shops (especially the new department stores), as well as shop window displays and street lighting. And these were exactly the sort of places that Vaseline glass would have been on show. In the glassworks itself, perhaps and in the large hotels and exhibition halls where Trade Shows were staged.

Crucially, arc lamps were extensively used in showrooms, department stores, and retail establishments of all kinds.

They emitted brilliant light with a blue-violet glow, that enabled customers to see the goods (much better than dim gas lamps) and they extended the opening hours for trading.

They emitted brilliant light with a blue-violet glow, that enabled customers to see the goods (much better than dim gas lamps) and they extended the opening hours for trading.

|

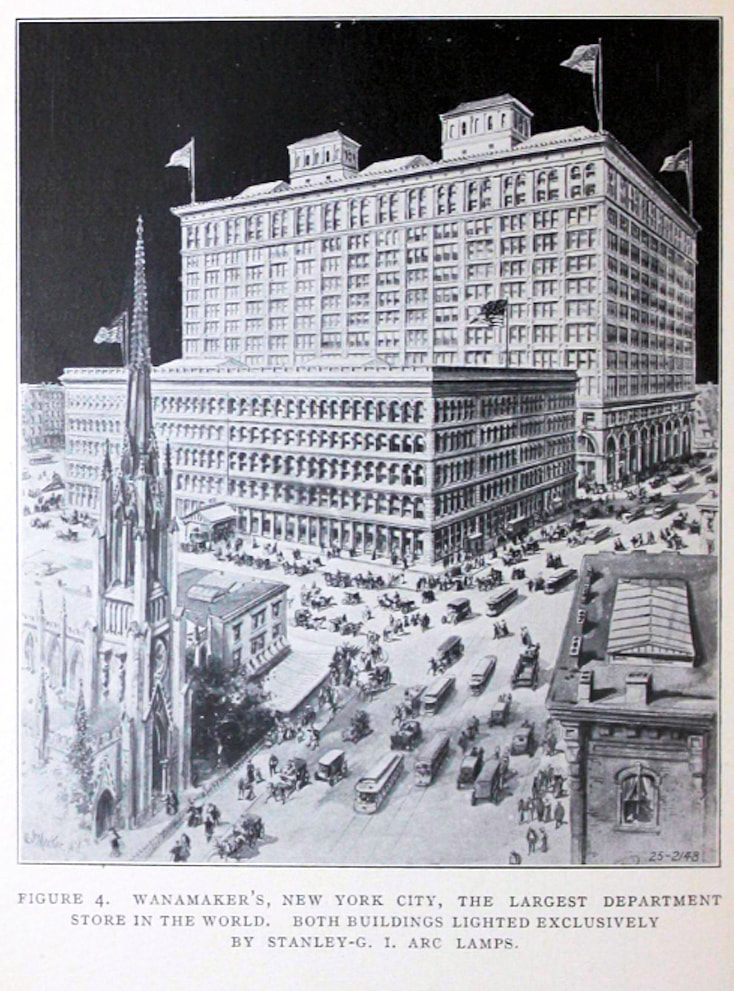

In 1878, one of the first department stores in the USA, Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, became the first to install arc lamps on the retail floor. Customers were thrilled, and the owner, John Wanamaker, knew he had been right when (two years earlier) he had spotted the marketing potential of a store illuminated by electric light at a lighting exhibit at the World Fair in Philadelphia. Wanamaker’s had a popular and greatly enlarged section for china and glassware in its store, that included tableware, vases and ornaments. It covered an entire, long section of the main ground floor, immediately by one of the three main Market Street entrances in Philadelphia. The arc lamps must have illuminated it brilliantly. Other stores followed - Marshall Field brought in arc lights in 1882 and Siegel Cooper’s shiny new department store boasted it had 800 big arc lights. Imagine the glow in the glass section! |

Above, left: the arc lamp was still popular in 1908, especially for retail stores, as this ad in the “Merchants Record and Show Window” journal demonstrates.

Above, right: Taken from a 1908 “Stanley G Arc Lamp” booklet, the illustration above shows Wanamaker’s New York store was lit “exclusively by arc lamps”.

Above, right: Taken from a 1908 “Stanley G Arc Lamp” booklet, the illustration above shows Wanamaker’s New York store was lit “exclusively by arc lamps”.

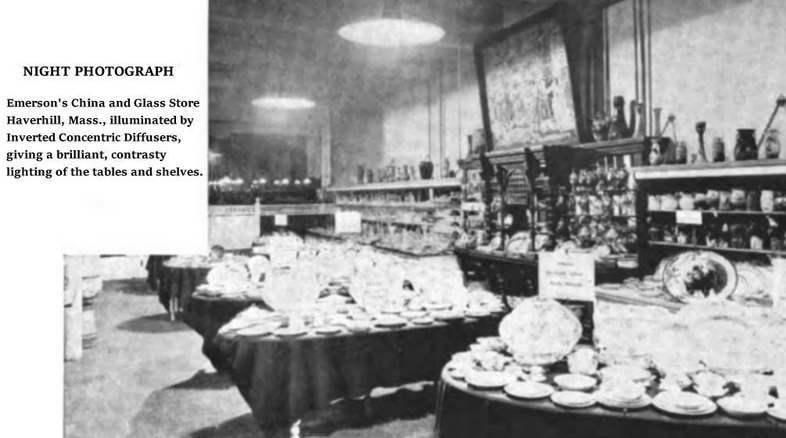

The brilliance of the arc lighting is clear from this 1905 photo taken inside Emerson's China and Glass Store in 1905

Arc lights were also used to illuminate splendid shop window displays. The art of window dressing was extremely important, and elaborate set pieces were designed to show off the goods (a crucial marketing strategy in the days before radio and television advertising). And with arc lighting on many town centre streets too, imagine just what a display of Vaseline glass might have looked like, glowing vividly on a dark night, illuminated by the light of all the arc lamps. Customers would have seen these magical effects on the glass and likely purchased accordingly – possibly being just a little disappointed later when they looked at their glass in their own homes without the arc lighting!

|

But arc lights had problems too. They weren’t entirely safe, they were noisy and they cast a bright but often harsh, blue-purplish white light. The emergence of the incandescent light bulb (with its softer and more flattering golden light that had no UV rays) eventually won the race, although arc lights were used in retail stores well into the early 1900s, and even longer for outdoor lighting.

It’s interesting to note that when arc lamps dominated the lighting scene, Vaseline glass was also very popular. As the use of arc lamps dwindled, so did the popularity of Vaseline glass. It may be purely coincidental, of course. But there’s no denying the impact of that 1897 newspaper report describing the “magnificent green fluorescence” on the glass under electric arc lighting. Classic Vaseline Carnival Glass was made by various glassmakers. It is not particularly common, as they all appeared to make it in relatively small quantities. Fenton made the most, but it's not always easy to spot if there is a heavy iridescence. It is harder to find examples that were made by Northwood, Millersburg, Imperial or Sowerby. There are some scarce European examples, like the rare Pebble and Fan, and Seagulls bulbous vases that were most probably made by Libochovice (Czechoslovakia). A few rare examples of the Tornado Variant are known with the applied "tornadoes" being in Vaseline. Above left, Feather and Heart pitcher, by Millersburg, and

on the right a Concave Diamonds tumbler by Northwood. |

|

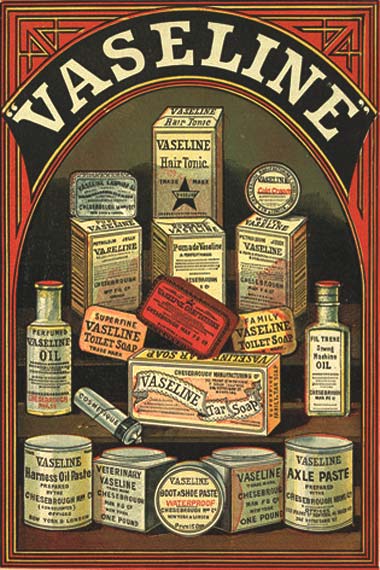

Footnote: where did Vaseline glass get its name from? And when was “Uranium Glass” first called Vaseline Glass? Clearly the name is a reference to the brand name for the original Chesebrough petroleum jelly. In his U.S. Patent in 1872, he wrote: "I, Robert Chesebrough, have invented a new and useful product from petroleum which I have named Vaseline..." In fact he had named it before that, according to a 1912 ad for the product, which cited the “naming” date as 1869. But why was it called “Vaseline”? There are all sorts of theories about the origins of the word. We think that this one by A.M. Rontrey writing in 1894 about the trademark protection that Chesebrough was trying to establish, sounds most likely: “the name Vaseline appears to me (in its mixed etymology) to have been compounded of VÂSE (the French for ooze) and the much abused terminal ine preceded by an a for the sake of euphony. (From an 1894 journal “The American Druggist”.) The yellowish-greeny colour of Vaseline petroleum jelly clearly inspired the name of the glass colour. We see Fenton ads from 1937 and 1938 showing the colour Vaseline for their glassware, as well as listings from New York Auction Rooms in 1927. Even earlier, in 1924, is this mention in “Old Glass” by Hudson Moore, which states (pejoratively) that “no real collector” would ever use the term “Vaseline, a dealer’s term”. So clearly, the antique or glass dealers were referring to uranium glass as “Vaseline” in the early 1920s. |