The Discovery of Iridescence on Glass

© Glen and Stephen Thistlewood, originally published October 2017. Updated June 2024.

Iridescence is the heart and soul of Carnival Glass.

Its shimmering beauty thrills collectors and provokes passionate response. But who or where was iridescence on glass "discovered"? How did it come about?

Iridescence is the heart and soul of Carnival Glass.

Its shimmering beauty thrills collectors and provokes passionate response. But who or where was iridescence on glass "discovered"? How did it come about?

Iridescent Glass

Left: Ancient Iridescent Roman Glass, courtesy and copyright, Robert Deveau Galleries.

Centre: Carnival Glass for the Millions: a century of production.

Right: Fenton's Favrene - a Contemporary celebration of Tiffany's Favrile glass. This picture is in recognition of our dear friend,

(the late) Howard Seufer without whose skill, intense dedication and knowledge of glass production at Fenton, it could not have been made.

Left: Ancient Iridescent Roman Glass, courtesy and copyright, Robert Deveau Galleries.

Centre: Carnival Glass for the Millions: a century of production.

Right: Fenton's Favrene - a Contemporary celebration of Tiffany's Favrile glass. This picture is in recognition of our dear friend,

(the late) Howard Seufer without whose skill, intense dedication and knowledge of glass production at Fenton, it could not have been made.

Ancient Roman glass can be found with the soft glimmer of gentle iridescence (see above left), but the cause of that iridescent shimmer was accidental, brought about by the decomposition of the glass over the centuries.

|

But what about glass that was intentionally made iridescent? When and where was the first ground breaking, deliberate use of iridescence on glass: it set the scene for Art Glass for the Few, which grew into Carnival Glass for the Millions.

Jabir ibn Hayyan (aka Geber) Intrigued by our work on Pantocsek (see later in this Article), James Evans, a researcher in gemology, contacted us. He pointed us towards some fascinating documents that suggested iridescence on glass could have been intentionally produced as early as the 8th century in Persia/Mesopotamia. A series of books, written by the noted alchemist, Jabir ibn Hayyan (shown right) – who was also known by many as “The Father of Chemistry” – included a treatise on coloured glass that had a specific section on Lustre Glass. The online translation gave specific recipes including one for “abu qalmun” that had “unique iridescent colours”. ("abu qalmun" has several meanings, which include chameleon-like or light/colour variations as seen on peacock feathers.) The ingredients in the recipe include marcasite (iron sulphide), haematite (iron oxide compound), iron saffron and iron scales. The method involved pulverizing the ingredients, mixing them with wine vinegar and borax, adding what we might call cullet and then placing the mixture in a glass-makers furnace. The recipe ended with the words “Light a very strong fire and you will obtain ‘abu qalmun’ which keeps changing colours.” We are not qualified to comment on the date and authenticity of this work, however, there’s no doubt that the ingredients and suggested method make sense. Iron (as ferric chloride) in solution was sprayed onto very hot glass, to make Carnival. The ingredients and method in that early treatise sound a little similar. We have not seen any examples of “abu qalmun” glass that might have been made, but as it was the 8th century, it’s unlikely there is any in existence, although some is rumoured to exist. A similar technique was apparently applied to ceramics at the same time, and some rare examples of lusterware ceramics are indeed known. The conclusion is that it seems entirely possible that glass was intentionally iridised using iron salts in solution and intense heat as long ago as the 8th century. |

Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber), Arabian alchemist. Courtesy and source Wellcome Collection. Public Domain.

|

|

Leo Valentin Pantocsek … it’s not a name that trips easily off the tongue, but remember it, because Pantocsek (pronounced Panto-check) was the person responsible for advancing the use of iridescence on glass.

Pantocsek, a scientist, was born in 1812 at Kielce, in the heart of Poland. In 1848 he moved to, and settled in Hungary (then part of the Austrian Empire). He began working at J.G. Zahn’s Zlatno based glassworks (established in 1836). It was here, probably around 1856, that Pantocsek created a technique for iridising glass. The World's Fair, London, 1862. According to Attila Sik, Hungarian glass researcher, these “first iridescent works were shown and lauded at the lesser-known 1862 World's Fair [International Exposition] in London”. So, in 1862, some seven years after Pantocsek's discovery, we have the world’s first major showing of iridescent glass. The glass was created by L.V. Pantocsek and made at J.G. Zahn's Zlatno Glassworks. |

A panoramic view of the 1862 World's Fair, London. Public domain, Wikimedia. The attendance was over 6 Million visitors!

|

Previously, we had understood that Josef and Ludwig Lobmeyr, the renowned Viennese glass company, were the first to use iridescence on glass, but here’s how Attila Sik explains events: “the opportunity was spotted by the Austrian Josef Lobmeyr and his brother who owned the esteemed glass company J&L Lobmeyr in Vienna. They saw a future in the glass finish and ‘enticed’ one of Pantocsek’s glass-making colleagues away and thus learned how to make iridised glass. There's more about the iridising processes here: "What is iridescence?".

The Lobmeyr brothers passed their information on to their brother-in-law, Wilhelm Kralik, who produced the glass for them at his factory. In 1873, Lobmeyr displayed a huge range of iridescent glass at the World’s Fair in Vienna where it received international attention and met with great success.”

After reading Attila Sik’s fascinating article on Pantocsek, we realised that the Lobmeyr brothers had not actually been the originators of the iridising technique, but instead, they had been the businessmen who saw and developed its phenomenal potential.

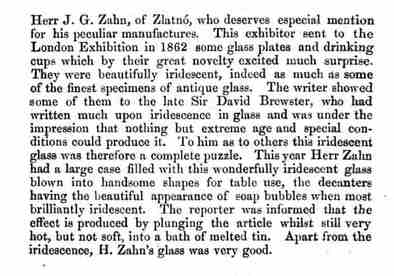

The Official Report - we have discovered a fascinating official report made in 1874 by the British Royal Commission. Shown below is the key extract, where

Previously, we had understood that Josef and Ludwig Lobmeyr, the renowned Viennese glass company, were the first to use iridescence on glass, but here’s how Attila Sik explains events: “the opportunity was spotted by the Austrian Josef Lobmeyr and his brother who owned the esteemed glass company J&L Lobmeyr in Vienna. They saw a future in the glass finish and ‘enticed’ one of Pantocsek’s glass-making colleagues away and thus learned how to make iridised glass. There's more about the iridising processes here: "What is iridescence?".

The Lobmeyr brothers passed their information on to their brother-in-law, Wilhelm Kralik, who produced the glass for them at his factory. In 1873, Lobmeyr displayed a huge range of iridescent glass at the World’s Fair in Vienna where it received international attention and met with great success.”

After reading Attila Sik’s fascinating article on Pantocsek, we realised that the Lobmeyr brothers had not actually been the originators of the iridising technique, but instead, they had been the businessmen who saw and developed its phenomenal potential.

The Official Report - we have discovered a fascinating official report made in 1874 by the British Royal Commission. Shown below is the key extract, where

|

it described the ground-breaking display of iridescent glass by the Zahn Glassworks. Although Pantocsek made the first examples, he does not even get a mention! The credit is given solely to Mr. J. G. Zahn.

|

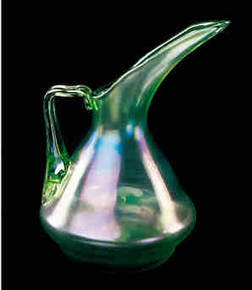

Ewer in iridescent glass believed to be by J.G.Zahn’s Zlatno glassworks. Courtesy Uvegcsodak.

|

The astonishing significance of this 150 year old report cannot be over-stated. Not only does it describe a display of the first intentionally iridised glass, but the reader is also told how it was done! The “very hot” glass was placed in molten tin … the iridescence came from stannous chloride (tin chloride).

The World's Fair (The World Exposition), 1873, Vienna

J&L Lobmeyr presented a major display of iridescent glass - attendance over 7 Million visitors.

At the World's Fairs, the exhibits were divided into main classes, and in each class prizes and medals were awarded. It was a great honour to receive these

J&L Lobmeyr presented a major display of iridescent glass - attendance over 7 Million visitors.

At the World's Fairs, the exhibits were divided into main classes, and in each class prizes and medals were awarded. It was a great honour to receive these

|

illustrious, international awards, and for a manufacturer, it bestowed prestige and boosted business.

In 1873 at the Vienna World's Fair, Ludwig Lobmeyr (J&L Lobmeyr, Vienna – described as the “Imperial Royal Glass Merchant”) was on the Glass Awards Jury. That meant he could (and indeed did) exhibit and display his company’s glassware, but he was not able to receive medals, other than what was termed an “Hors de Concours”, a sort of honorary merit. J.G. Zahn from the Zlatno Glassworks also had a display again, but it was overshadowed by the astonishing display of glass put on by Lobmeyrs, an example of which is shown below (from “Art & Arts at the Viennese World Exhibition, 1873”, Von Lutzow). |

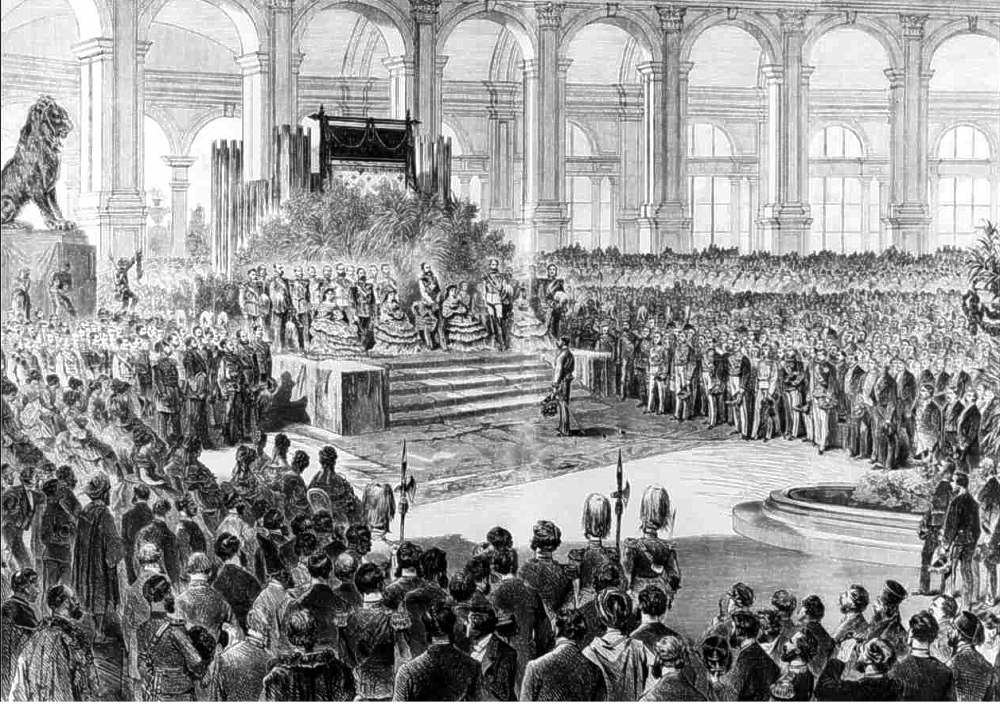

May 1st. 1873: the Opening Ceremony of the World's Fair in Vienna, Austria.

Archduke Karl Ludwig welcomes the Kaiser and prominent guests from all over the world, and where J&L Lobmeyr presents a major display of iridescent glass. The attendance was over 7 Million visitors. Wood engraving of a drawing by Vinzenz Katzlers. Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons Here’s how Lobmeyr's display was described in the Official Report of the Vienna Expo. “The greatest merit was in producing the greatest variety of beautiful objects, and in this respect the most important exhibitor, Herr Lobmeyr, glass maker to his Imperial and Royal Majesty the Emperor, has not been mentioned because as a juror, he was not entitled to compete”. There's no doubt the Lobmeyrs’ impressive iridescent glass display had a major impact on other glassmakers. It won “universal admiration”, and just over a third of the glass objects featured in an illustrated book of the Expo exhibits were from J&L Lobmeyr! Of course, this was their home territory - they were located in Vienna, literally just around the corner! They didn’t have to transport their glass over vast distances. |

|

Another important exhibitor at the Vienna Expo was Edward Moore, from the Tyne Flint Glassworks, South Shields (England). Moore’s glass was distinctive for two reasons: firstly, in an overwhelming ocean of hand-made Art Glass, Moore was displaying pressed glass – and secondly, his pressed glass (a form of glass often deprecated at that time) was praised for its excellent quality. But for Carnival Glass history, the appearance of Edward Moore at the 1873 Expo was of major importance. Edward Moore would have seen for himself, the amazing new iridescent effects that could be produced on glass. Moore was a passionate experimenter and “colourist”. He loved to achieve new shades on his glass. We believe that Moore produced the very first press moulded, patterned and iridised glass in c. 1880s – in other words, the very first Carnival Glass. It appears very likely that the 1873 World Expo in Vienna was where he was first inspired to create it, having seen the iridised Art Glass made by Zahn and by Lobmeyr. On the right is Moore’s Tiny Daisy creamer with marigold iridescence on Vaseline base glass. It is believed to have been made in the 1880s. There is much more about this intriguing item in our Collectors Facts. |

The World's Fair (The International Exhibition), 1876, Philadelphia

|

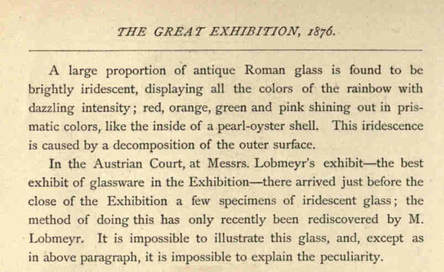

Lobmeyr stuns visitors with a last-minute display of iridescent glass.

Attendance over 10 Million visitors. J&L Lobmeyr exhibited again at the incredibly popular Philadelphia International Exhibition of 1876. According to the Official Report of the Fair) it appears that Lobmeyr claimed that his firm had “only recently rediscovered” the creation of iridescent glass. There was no mention of its production by J.G. Zahn at Zlatno (and that small company did not travel to Philadelphia to exhibit). It seems that Lobmeyr was now being identified with the “discovery” of creating iridescent glass! Above: extract from “The Great Centennial Exhibition - Critically

Described and Illustrated” by Phillip T. Sandhurst. Philadelphia, 1876 |

The World's Fair (The Paris Universal Exposition), 1878, Paris

Much Iridescent Glass on display from a wide range of European producers. Attendance over 16 Million visitors.

By 1878, many makers were producing iridescent glass. The official report on the Paris Expo stated, in fulsome language:

Much Iridescent Glass on display from a wide range of European producers. Attendance over 16 Million visitors.

By 1878, many makers were producing iridescent glass. The official report on the Paris Expo stated, in fulsome language:

|

“Lustred or Iridescent glass” … This form of decorative glass, which was shown by a few examples by Lobmeyr in the Austrian section at Philadelphia in 1876, has now become very abundant and common. It has been made in great quantities of late, and it may be seen in the shop windows in London, the small globes being generally filled with water to enhance the colored effect. The brilliancy of the iridescence has late been perfected and increased, and it is most satisfactory when seem in shadow and not in full light. Chandeliers and decorative bulbous plates of this kind of glass are extremely brilliant. Even black beads for trimmings of ladies’ costumes are now made as iridescent as peacock coal”. |

Above: Panorama des Palais by Fougere, 1878. Public Domain. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

|

|

In fact, the Austrian section of the Expo was dominated by Lobmeyr, taking up over half of the available space. A report about the Expo (in “Glass and Glass Ware” Paris, W. Blake & C Colné, 1878) described Lobmeyr as “the pioneer” of iridescent glass, and explained that “by using fire works in a furnace where some glass-ware had been placed the metallic vapors of these fireworks produced a peculiar iridescent color upon the glass”.

This seems to conflict with what we have now learned about Pantocsek’s earlier pioneering work! However, at this point, it appears that Lobmeyr had more or less assumed (indeed, had claimed) the role of inventor or creator of iridescence on glass. The high profile of J&L Lobmeyr’s company surely gave it a presence that J.G. Zahn’s smaller factory in Zlatno could not compete with. The business acumen of the Lobmeyrs ensured that they seized upon the potential of the new iridised glass, and built upon it … and that seems to have worked, as the name Lobmeyr appears to have become synonymous with iridescent glass by the late 1870s. The English firm of Thomas Webb & Sons, from Stourbridge, made a great impression at the Paris 1878 Expo, in fact the exhibition’s illustrated catalogue stated that "Messrs. Thomas Webb and Co of Stourbridge are the best makers of glass in the world”. The previous year, 1877, had seen Webb patenting “an improved means of producing iridescent colours on glass” (quote from the 1877 “London Gazette”). Iridescent glass was a big thing for Webb; their famous “Iris” (golden) and “Bronze” (dark) lines, shimmered with iridescence. |

English iridescent glass – the piece on the left is etched Webbs Iris.

The other two vases are almost certainly Stourbridge pieces. |

|

On to Tiffany … and Carnival Glass

An article in an 1880 Australian newspaper summed up the situation at the time perfectly: “The iridescent properties of the Bohemian glassware remained for a long time a speciality of Bohemian manufacture, and still is a great feature, although English firms have, since its discovery, successfully imitated it”. (From “The Week”, a Brisbane newspaper, reporting on the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition). First in Bohemia and then in England, iridescent glass became a success. Soon afterwards, its attractions caught the eye of Louis Comfort Tiffany in the USA, and in 1894, Tiffany’s iridescent Favrile glass was introduced. It was a knockout success! But it came at a price, it was “upmarket” and exclusive, retailing in 1900 from $2 for a small item, upwards (which would be around $55 upwards today). Tiffany lamps were advertised in 1905 as costing from $17 to $750 (around $440 to $20,000 equivalent today). Tiffany fiercely protected his iridescent glass and attempted to stop others creating similar effects. The “Crockery & Glass Journal” reported in 1906 that Tiffany had taken out a temporary injunction against five department stores “restraining them from selling or offering for sale certain glassware which it is alleged is an imitation of that made at the Tiffany Studios”. Right: a 1900 ad for Tiffany’s Favrile Glass in the “New York Daily Tribune”. Far right: a Tiffany Favrile oil lamp and shade, 1900, exhibited in the Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Illinois, USA. By Daderot (Own work) Creative Commons [Public domain or CC0], via Wikimedia Commons. |

|

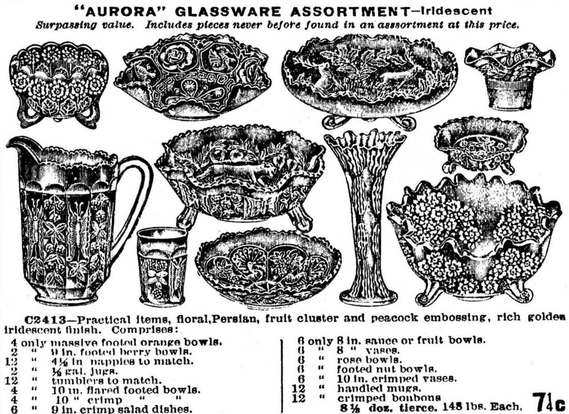

The mass production of Carnival Glass begins.

In West Virginia in 1907, Fenton began to iridise pressed glass, calling it “iridie” or “iridill” - glass that had a metallic lustre. How frustrating it must have been for Tiffany to see this new, iridescent pressed glass being openly described as “Tiffany Iridescent Glass”, like in this 1910 Washington Times ad. below, centre, for "Flower Holders". In fact, the vase in the ad was Carnival Glass – press moulded and iridised: it was Westmoreland’s “Corinth” vase. Some advertisers and merchants were promoting the emerging Carnival Glass as “Tiffany” or “Imitation Tiffany ware”, and the prices were so low compared to Tiffany's upmarket pieces. |

Westmoreland Corinth vase. Courtesy Joan Doty

|

|

In 1913, Tiffany brought a law suit against Carder, who was making iridescent glass at his Steuben Glass Works, but as iridising glass was a well-known process by then, Tiffany could lay no claim to its invention, and the matter was settled out of court. And by that time it was already too late of course, as Carnival Glass had been around since 1907 - in the USA, Fenton, Northwood, Imperial, Dugan, Millersburg and a number of others had already mass-produced it, and its production spread all around the world.

The “Crockery & Glass Journal” expressed the situation perfectly in 1913 when they wrote that Imperial’s "Nuart glass [a Carnival Glass range that included the Homestead design on the left] comes so near the Tiffany Favrile product that few can tell the difference”. Tiffany’s competitor in the iridescent Art Glass market, Frederick Carder, was also not pleased by the output of affordable iridised glassware. He stated that “when the maid could possess iridescent glass as well as her mistress, the latter promptly lost interest in it”. Peevish, yes, - but understandable - as Carder and Tiffany were supplying the rich echelon. But beauty is no respecter of wealth. Shimmering iridescence on glass was made both available and affordable to everyone, thanks to the makers of (what we now know as) Carnival Glass. A touch of Irony! We saw how the World's Fair of 1862 in London displayed the first deliberate creation of iridescent glass by Pantocsek at J.G. Zahn’s Zlatno glassworks in the mid 1850s, and how J&L Lobmeyr built on Pantocsek's pioneering work, sharing the glories of iridescent glass to a wider audience. Thomas Webb & Sons patented their version of iridescent glass in 1877, and exhibited it in 1878 at the Paris Expo. Edward Moore in England experimented with iridescence in the 1880s, producing the very first examples of Carnival Glass … but that was not to last. |

Imperial Homestead plate in amber,

marked "Nuart". Courtesy Seek Auctions |

|

Others in Bohemia and England, such as Loetz, Kralik, and Stevens & Williams made their own versions of iridescent glass. And then Louis Comfort Tiffany came on the scene and “owned it” for a few years … until, that is, the advent of Carnival Glass in around 1907. Carnival Glass collectors owe a lot to the wholesale catalogue company, Butler Brothers of Broadway, New York - their catalogues provide invaluable information about the Carnival Glass that was being made, and sold, in the USA in the early 1900s, and the patterns from the different glassmakers. In an ironic twist, playing to the popularity of the World's Fairs, Butler Brothers announced their own exposition in 1913 - a semi-annual "World's Exposition", proudly boasting it to be "undoubtedly the greatest exposition of ... general merchandise ever collected for the inspection and use of the Retailers of America ... with an exposition hall for every country and maker". Included in their 1913 catalogue were some truly amazing assortments of Carnival Glass - spectacular in their range of shapes and in their ingenuity of pattern designs. Iridescent Glass had truly come into its own, and production spanned the World. Glassmakers across the globe had turned iridescent glass from being a luxury for the few, to beauty for the many. |

Above: Butler Brothers 1913 "World's Exposition"

|

The wheel turns full circle

Earlier, we referred to Tiffany's "Favrile" iridescent glass made in the early 1900s. In recent times, contemporary glassmakers have re-created the look and style of Favrile. In 1991, Fenton decided to recreate a version of the two early glass formulas, Tiffany's Favrile and Steuben's Blue Aurene. Fenton developed

Earlier, we referred to Tiffany's "Favrile" iridescent glass made in the early 1900s. In recent times, contemporary glassmakers have re-created the look and style of Favrile. In 1991, Fenton decided to recreate a version of the two early glass formulas, Tiffany's Favrile and Steuben's Blue Aurene. Fenton developed

|

"Favrene", a gorgeously iridised silvery blue colour.

Favrene was technically very difficult to make, requiring a special reheating process was necessary to coax the silvery layer to the surface of the glass - but the effect is spectacular! Other artisan glassmakers, like Isle of Wight Glass in England, also produced some sumptuous iridised studio glass, like the sea shells shown on the right. Above: Fenton's Two Seasons vase in Favrene.

The mould was one of many acquired by Fenton from Holophane/Verlys. We have a major, fully illustrated feature on Fenton's use of ex-Verlys moulds, here: Fenton and Verlys. |

Above: Sea Shells made by Isle of Wight Glass

Below: a Fenton Favrene Snail |

Wonderful Contemporary Carnival Glass, reflecting the long heritage of creating amazing iridised glass.

Wonderful Contemporary Carnival Glass, reflecting the long heritage of creating amazing iridised glass.

A Side Note on Iridising

While Pantocsek’s original iridising method at J.G. Zahn’s Zlatno Glassworks had utilised stannous chloride, the golden tones (what today’s collectors call “marigold”) came from the use of ferric chloride (from iron), which of course, was a technique used by Jabir ibn Hayyan.

The renowned maker of Classic Carnival Glass, Harry Northwood, explained it perfectly: "Ordinary Chloride of Iron as bought at wholesale drug stores costs 3½ cents a lb. ... spray on glass when finished ready for lehr... glass must be fairly hot."** Harry added some extra tips: "Spray on glass very hot for Matt Iridescent and not so hot for Bright Iridescent" which is how satin (matt) and radium (bright) effects were achieved on Carnival. One extra tip that Harry Northwood gave is a very interesting one indeed. He explained that spraying iron chloride on hot glass, quickly followed by a second spraying with a tin solution "gives beautiful effects". The tin solution is stannous chloride – originally used by Pantocsek and much used by glass makers today to produce shimmering iridescent effects that are often quite light and without the heavy “staining” produced by the iron salts. It seems most likely that this double doping of a light ferric chloride spray followed by a stannous chloride spray may indeed have been what gave rise to the magnificent effect known as pastel marigold, as seen on this Northwood Peacocks plate.

A Side Note on Iridising

While Pantocsek’s original iridising method at J.G. Zahn’s Zlatno Glassworks had utilised stannous chloride, the golden tones (what today’s collectors call “marigold”) came from the use of ferric chloride (from iron), which of course, was a technique used by Jabir ibn Hayyan.

The renowned maker of Classic Carnival Glass, Harry Northwood, explained it perfectly: "Ordinary Chloride of Iron as bought at wholesale drug stores costs 3½ cents a lb. ... spray on glass when finished ready for lehr... glass must be fairly hot."** Harry added some extra tips: "Spray on glass very hot for Matt Iridescent and not so hot for Bright Iridescent" which is how satin (matt) and radium (bright) effects were achieved on Carnival. One extra tip that Harry Northwood gave is a very interesting one indeed. He explained that spraying iron chloride on hot glass, quickly followed by a second spraying with a tin solution "gives beautiful effects". The tin solution is stannous chloride – originally used by Pantocsek and much used by glass makers today to produce shimmering iridescent effects that are often quite light and without the heavy “staining” produced by the iron salts. It seems most likely that this double doping of a light ferric chloride spray followed by a stannous chloride spray may indeed have been what gave rise to the magnificent effect known as pastel marigold, as seen on this Northwood Peacocks plate.