What is a "straw mark"?

|

Carnival Glass collecting has its “urban myths” just like everything else – take the story behind the (incorrectly used) term “straw mark” for example.

Sometimes, when you look look at a piece of glass, you can see a short, straight mark, about an inch long, on the surface of their glass. These marks are much more visible and obvious on Carnival Glass, as the iridescent surface emphasises their appearance, especially if they occur in a plain section of the design. The small Fenton Pine Cone plate on the left is a perfect example. It's a super little plate, with great pattern detail and wonderful iridescence. But right there in the very centre and in only blank space on the whole piece - is what gets called a straw mark! At first sight the mark may cause alarm, and they can be a little unsightly. Could it be a crack? No - but what caused it? The Myths There are several variations of the same myth that is used to explain the mark: a piece of straw got into the mould whilst the glass was being made and caused the mark, or a piece of straw got stuck to the still-warm glass cooling in the lehr and caused the mark, and even that it came from the straw that was used to pack the glass in. Of course, none of these explain the real reason. In fact if you think of the very high temperature of glass whilst it was being made, it’s obvious that any pieces of straw would immediately burn right off, and straw packing is never going to cause an indentation in the hard glass surface. |

The Answer - what did cause "straw marks"?

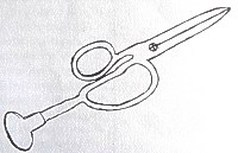

The correct name for the mark is a shear mark, which indicates clearly what made it. Glassmakers used shears to cut off the gather of molten glass as it was being dropped into the mould ready to be pressed - see below left. Because the blades of the shears were relatively cool, the act of cutting the very hot glass resulted in a fractional cooling and resultant hardening of the surface of the glass where it was cut. This is the shear mark - seen in close-up, below centre - which is most obvious where the design has large plain, pattern-free areas.

With skill on behalf of the presser, the shear mark could be hidden - either within the intricacies of the pattern, or by expert "flipping" of the gob of molten glass so the shear mark was not on the surface. The mark could also be removed by re-heating the pressed item and "fire-polishing" the mark out.

However, judging by the number of shear marks that are visible on Carnival Glass pieces, this was not always done, whether it was down to lack of skill, time or the lack of quality control.

In the 1950s, a dome shaped extension was added to the handle on glassmaker’s shears (below, right), which was used to smooth out the shear mark after the hot glass had been dropped into the mould.

The correct name for the mark is a shear mark, which indicates clearly what made it. Glassmakers used shears to cut off the gather of molten glass as it was being dropped into the mould ready to be pressed - see below left. Because the blades of the shears were relatively cool, the act of cutting the very hot glass resulted in a fractional cooling and resultant hardening of the surface of the glass where it was cut. This is the shear mark - seen in close-up, below centre - which is most obvious where the design has large plain, pattern-free areas.

With skill on behalf of the presser, the shear mark could be hidden - either within the intricacies of the pattern, or by expert "flipping" of the gob of molten glass so the shear mark was not on the surface. The mark could also be removed by re-heating the pressed item and "fire-polishing" the mark out.

However, judging by the number of shear marks that are visible on Carnival Glass pieces, this was not always done, whether it was down to lack of skill, time or the lack of quality control.

In the 1950s, a dome shaped extension was added to the handle on glassmaker’s shears (below, right), which was used to smooth out the shear mark after the hot glass had been dropped into the mould.

Further Reading

Much of the earlier production of Classic Carnival Glass is already over 100 years old. Unsurprisingly therefore, some pieces will have damage, ranging from the very obvious – such as a large chip or even a broken foot or handle – to the less significant, for which collectors have developed a whole vocabulary of descriptions, such as chip, flake, flea-bite, chigger, rough spot, and even “no-harm” damage.

However, there are many features of pressed glass, just like Straw Marks, which simply reflect the way that it was actually made. Such features (especially the more serious or obvious ones) may be looked at as some sort of damage, but they are the result of various glass-making processes – at a time when “quality control” was less rigorous than modern-day consumers would expect.

All is explained here: Features (and defects) of handmade pressed Carnival Glass, by Glass Engineer (the late) Howard Seufer.

Much of the earlier production of Classic Carnival Glass is already over 100 years old. Unsurprisingly therefore, some pieces will have damage, ranging from the very obvious – such as a large chip or even a broken foot or handle – to the less significant, for which collectors have developed a whole vocabulary of descriptions, such as chip, flake, flea-bite, chigger, rough spot, and even “no-harm” damage.

However, there are many features of pressed glass, just like Straw Marks, which simply reflect the way that it was actually made. Such features (especially the more serious or obvious ones) may be looked at as some sort of damage, but they are the result of various glass-making processes – at a time when “quality control” was less rigorous than modern-day consumers would expect.

All is explained here: Features (and defects) of handmade pressed Carnival Glass, by Glass Engineer (the late) Howard Seufer.