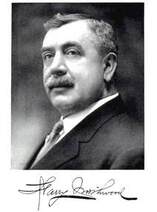

Harry Northwood - Triumph and Tragedy (Part One)

Harry Northwood - master glassmaker, at the height of his Carnival Glass fame in 1911, above left from the “History of Greater Wheeling”, 1911.

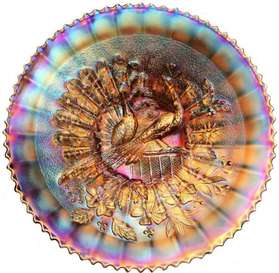

Centre and right: two of Northwood's amazing Carnival Glass designs: Poppy Show in pumpkin marigold and a lavender Poinsettia and Lattice.

Centre and right: two of Northwood's amazing Carnival Glass designs: Poppy Show in pumpkin marigold and a lavender Poinsettia and Lattice.

|

Sometimes you have to go through darkness to get to the light, but for Harry Northwood, it was almost certainly the other way around. Harry was a brilliant glassmaker – an inventor, artist, glass colourist and businessman. His Carnival Glass is often seen as the finest of all; his Peacocks design is artistically perfect (seen on the right). But it was the light – in the form of Harry’s Illuminating Glassware range called “Luna” that ultimately took Northwood into the darkest of days. |

|

The Brilliance of Illuminating Glassware Candles, kerosene lamps and gaslights all helped to illuminate the home a century ago, and it's no surprise that Carnival Glass makers exploited the market, producing a range of candle sticks and oil lamps. Northwood made the (now very collectable) Grape and Cable candle lamp (shown, right): cleverly the candle lamps consisted of a regular candle stick (available separately), with the addition of a metal frame and a shade. The shades are the hard part to find today, presumably because they were damaged or broken through regular use and the heat from the candles. Up until around 1910, the wholesale ads for Carnival Glass (and glass generally) were concentrated on lighting requirements being met by candle sticks (all shapes and sizes) and by oil / kerosene lamps (again all shapes and sizes, including the fabulous "Gone With The Wind" style oil lamps). But ... the world was changing! Candle sticks and oil lamps naturally had their drawbacks, and into the darkness came clean and (relatively) easy electric light! It’s hard to imagine our everyday life without electric lighting. Flick a switch and hey presto! |

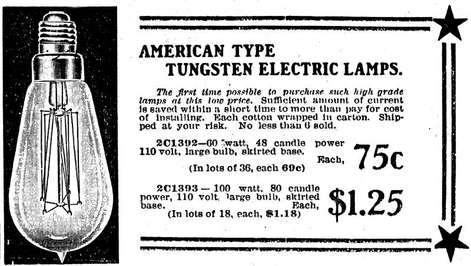

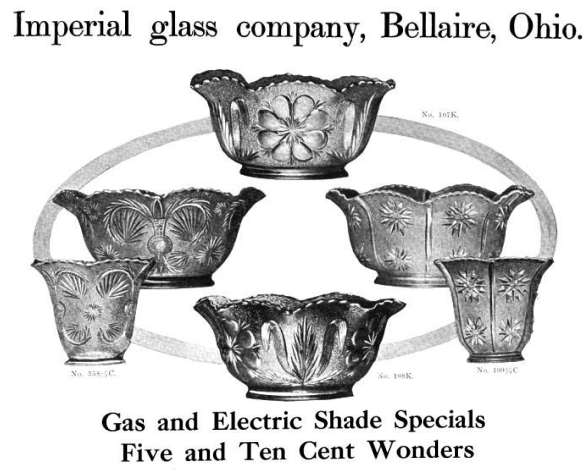

These two ads from early 1911, point to the changes that were about to unfold, to which the glassmakers had to react ... and quickly.

On the left is an ad for electric light bulbs in the Spring 1911 Butler Brothers wholesale catalogue. Note that although the lamps were individually "cotton wrapped", the shipping was at the buyer's risk - those early light bulbs, or the filaments inside them, must have been very fragile!

|

On the right is an ad by Imperial Glass in the January 1911 Pottery, Glass and Brass Salesman that was anticipating the demand for electric shades (as well as their existing gas shades). The Imperial shades were Mayflower and Starlyte in their new "Silver-green Iridescent effect" - Helios green Carnival (shade #358 in the ad, in two sizes on the left, is not known to us in Carnival). |

|

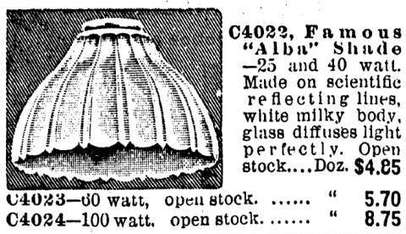

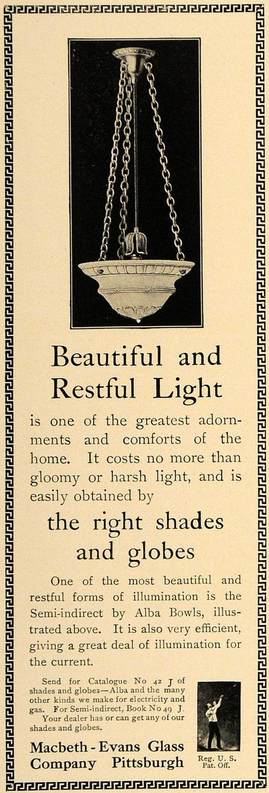

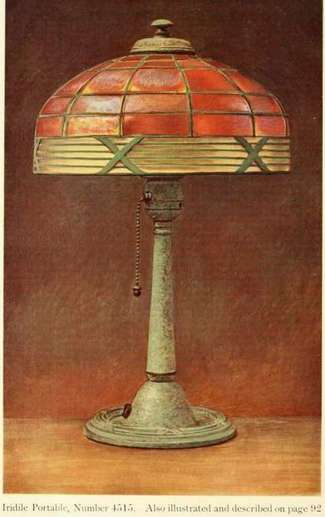

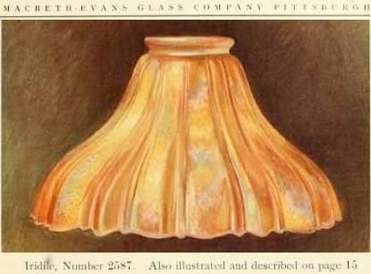

Electricity was very fashionable when it was first introduced commercially by Edison (in 1882 in lower Manhattan), so much so that Alice Vanderbilt appeared at an 1883 High Society Masquerade Ball in a gown that was called “Electric Light” (and yes, part of it actually lit up). Many of the glass makers saw a profitable niche in the market for the production of glass lampshades and associated items, for the new electric lights. Harry Northwood was one of those glass makers, and at this point our story could so easily have been a very ordinary and predictable one. Glass maker produces pretty glass shades ... glassmaker makes a lot of money ... job done! That’s surely how Harry intended it would work out, but the reality was very different. In fact our story takes a most unpredictable turn. Indeed, it becomes something of a tragedy for the Northwood firm, with unforeseen circumstances that may possibly have even contributed to two untimely deaths. To reveal the full story, let us first throw some light on the Illuminating Glassware market back in those early days, and we’ll also put the spotlight on some splendid Carnival Glass shades. The Macbeth-Evans Glass Company Our story starts with George Macbeth, a co-founder of the Macbeth-Evans glass empire, who was a respected figure in the glass industry, particularly in the specialised branch of lighting. The powerful "range lights" at each end of the Panama Canal were produced by Macbeth, as were many lighthouse lenses. In 1903, Macbeth invented a formula for a special kind of illuminating glass to be used for electric lampshades and globes. The glass was translucent, instead of densely opaque, and it diffused the electric light softly, providing gentle light that was not only practical but was also flattering. Not only was it for use inside the home, it was also intended for commercial use, public buildings and street lighting – a sound proposition with the possibility of major sales. Macbeth-Evans called their new range of glass lighting “Alba”, and on the right is an ad from 1912, for their "beautiful and restful" Alba shades and globes. As well as their "Alba" range, they also produced some beautiful iridescent shades in a glass they called “iridile” and a lighter toned one called “lustro”. Shown below is an ad from the Spring 1913 Butler Brothers wholesale catalogue. What is particularly unusual is that it specifically names the shade - the 'Famous "Alba" shade'. Mostly items in Butler Brothers were referred to more generally as "electric shade" or "gas shade": the Alba shade must have been seen as a particularly special or well-known item for it to be referred to by its brand name. |

Macbeth-Evans’ range of lighting

In 1912, Macbeth-Evans heavily promoted their extensive range of glassware in a catalogue called “Ornamental Street Lighting and Alba Globes”, and the following year, 1913, saw the publication of their “Shades and Globes” catalogue. Below are some examples of their wonderful shades, which used the "Alba" formula for the translucent base glass. As you can see, some of their shades also had enamelled decoration.

In 1912, Macbeth-Evans heavily promoted their extensive range of glassware in a catalogue called “Ornamental Street Lighting and Alba Globes”, and the following year, 1913, saw the publication of their “Shades and Globes” catalogue. Below are some examples of their wonderful shades, which used the "Alba" formula for the translucent base glass. As you can see, some of their shades also had enamelled decoration.

|

The problem for Macbeth-Evans (and Harry Northwood)

Although lighting was a very important part of Macbeth-Evans' business, they didn’t originally take out a patent on the formula for their Alba translucent glass despite it being such a key part of their range of lighting. As illuminating glassware became a hugely popular and profitable business for many glass firms, it was perhaps inevitable that a number of other glass makers produced their own versions of Alba style translucent glass. They came up with a variety of interesting names, such as “Ferlux”, “Delica White”, “Moonstone” and “Lucida”. Without doubt it was the fame of Alba that attracted Harry Northwood to make his own version, which he called "Luna", and we explore this in Part Two of "Triumph and Tragedy". On the right are two Northwood shades in the pattern we now call Pillar and Drape. The base glass is often referred to as "moonstone", and in fact it is Harry Northwood's "Luna". Incredibly, for all his skills as a glass maker, glass designer and businessman, the decision to produce and market Luna glass became a tragedy for Harry Northwood. |

Two sizes of Northwood's Pillar and Drape shades on Luna base glass.

The larger shade has "NORTHWOOD" moulded under the top rim. Courtesy of Seeck Auctions. |