Glassworkers Wanted!

In an earlier Article - Glass For Its Time - we looked at the social circumstances of the early 1900s when Classic Carnival Glass was being made, and the impact it had on the design and fashions of its time. Here, in contemporaneous ads and images, we explore the labour employed in the glass factories that made such amazingly wonderful and beautiful Carnival Glass.

|

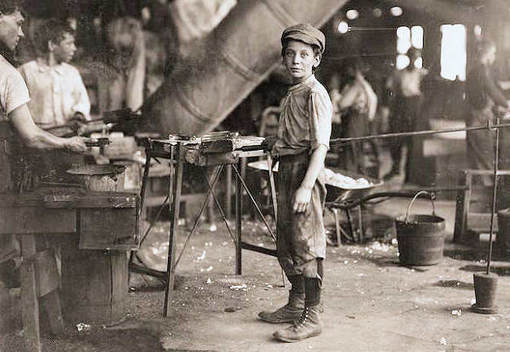

The photographs in this article (courtesy of the US Library of Congress) were taken by the American sociologist and photographer, Lewis Wickes Hine (1874 – 1940) who used his camera as a tool for reforming the US labour laws.

To gain entry to the mills, mines and factories, Hine assumed many guises: a fire inspector, postcard vendor, bible salesman, and even an industrial photographer making a record of factory machinery (source: Wikipedia). In American towns and cities, one of the most visible employment of children was in the so-called "street trades" - selling newspapers, carrying messages and the like - as we showed in our article Carriers Greetings: The Story Behind The Glass. However, like most of industry, agriculture and commerce of its time all around the world, US glasshouses employed unskilled labour including young workers and children under the age of fourteen. It was legal and normal for its time, and glass factories were no exception, as this photograph on the right shows us. However, a word of caution: the expression "boys" is a description that can easily be misunderstood, as it was often used as a general term for unskilled workers, irrespective of their age. |

A typical glass factory in operation, Indiana in 1908. Source: US Library of Congress.

|

|

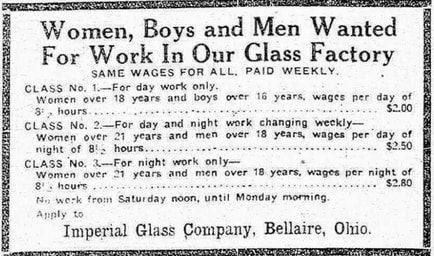

Above: a 1918 ad for workers to join Imperial Glass. Note how

wages were age related, and the premium for night work. |

A survey in 1910 revealed that 98% of the glass house boys were employed in the manufacture of pressed and blown ware. Boys were taken on to perform a variety of tasks, mostly on the factory floor where the extremely hot and arduous work was essentially a male environment in those days. Women and girls were employed to perform other work in the finishing rooms, areas where inspection, decorating and packing were carried out: it was thought that they would be more careful packing the finished ware in shipping barrels. The Influence of Unions The 1900 US Census showed that about 1 in 6 children (1.7 million) under the age of ten had "gainful occupations", and this is probably an understatement. However, reform was afoot: the National Child Labor Committee began pushing for change, and organised Unions were having an impact. The American Flint Glass Workers Union (AFGWU), formed in Pittsburgh in 1878, spread rapidly through the main glassmaking areas of the USA. It negotiated with employers and agreed very detailed and complex rules about working hours and conditions, and about pay rates that depended up the type of glass being made and the specific roles of each worker in a team of glassmakers. |

Below is a scene that could be found in pressed glassmaking shops in many parts of the world: this one is in West Virginia in 1908. The blurred figure (second from the right) is probably the "gatherer" who took the gob of molten glass from the furnace, and carried it to the "presser". The presser who is standing beside a side-lever press (on wheels) pressed the molten glass into the mould to form the glass item.

|

Glassmaking in West Virginia in 1908. Source: US Library of Congress.

|

The presser was assisted by a "turning-out boy" or a "mould-boy" who removed the item from the mould and placed it on a board. At that point, if the item was finished and ready to be taken to the lehr (for cooling and annealing), a "carrying-in boy" would perform the job. If a snap tool was required to hold the item, a "snapping-up boy" is on hand, and if further re-heating and finishing work was required, a "warming-in boy" would carry it to the glory hole. There might even be a "carrying-over boy" when the presser was some way away from the glory hole. The re-heated item was then delivered to the "finisher" who in this picture is seated. The finisher shaped/re-shaped the item into its final form. * A "lehr boy", seen in the centre of the picture with a long-handled board, took the finished item from the finisher and carried it to the lehr for cooling and annealing. * An additional process was needed to make Carnival Glass: after the finisher had completed his work, the item was taken to the glory hole again and re-heated. Then it was taken to be iridised (sprayed with a metallic salt solution known as "dope") before being taken to the lehr. |

So, in the team shown above, we have a number of skilled glassmakers - the gatherer, presser and finisher - and several other people who completed the semi-skilled or unskilled roles in the operation. Significant sections of the Union agreements set out how a team had to be made up. This helped to ensure that (lower paid) and less skilled workers and boys were not substituted for the skilled glassmakers' roles. There were also agreements on how many boys could be used in a team, as well as the maximum hours that the team could work (usually two "turns" or shift of 4½ hours per day).

On the left of the picture below, we can see other roles in the team that was making blow-moulded pieces. A glass-blower (often called the "gaffer") is blowing molten glass into a mould. The person to his right is the gatherer

|

who has brought the gob of molten glass from the furnace. A "mould boy" is seated in front of the gaffer: his job was to open and close the hinged blow-mould as required. The piece of hot glassware was removed from the end of the gaffer's blow iron by cracking it off. It was then clamped into a snap tool being held by the man standing on the right.

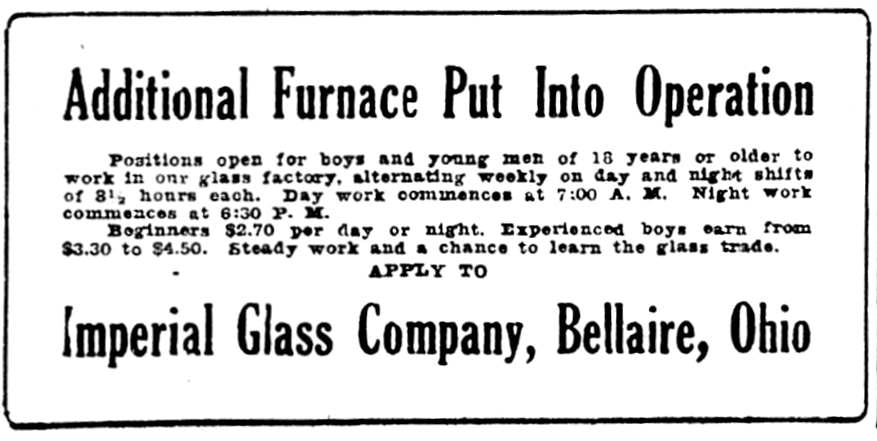

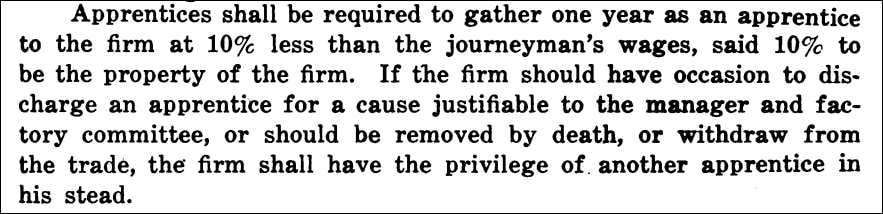

The AFGWU union also negotiated arrangements whereby unskilled boys could be trained and become apprentices (an essential step to becoming a skilled glassmaker on the highest rates of pay). Shown below is another ad for Imperial, this one from 1922. Note how it referred to "steady work and a chance to learn the glass trade". |

Making blow-moulded glass - West Virginia in 1908.

Source: US Library of Congress. |

Training and Apprenticeships

|

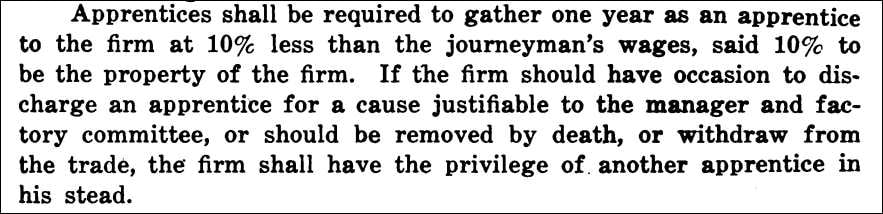

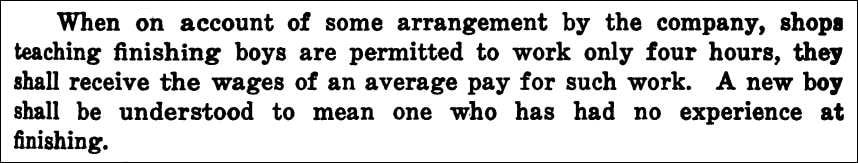

Shown below are two extracts from an AFGWU Agreement from 1917-18.The Union rules agreed with the glass factories were extensive - designed in part to protect workers' rights, and set out who could do what jobs in the factory.

Apprentices were the first step-up from unskilled boys' jobs and the rules ensured that a proper period of training was carried out - such as learning the skills of a gatherer. Clearly there could be resistance on the part of skilled workers taking time out to train the new boys - most workers were on "piece work" so any reduction in the turn's output cost the team money. The rule below was to compensate the team for reduced output.

In the picture on the right, we see a smartly dressed manager in a bowler hat and tie is supervising a very young-looking boy, whilst two other glassworkers assist. Such training obviously meant a loss in output, and a loss in wages

for the workers involved (as they were paid by the piece for the output produced). Hence the Union rules around compensating teams for lost wages. |

Above is an image from an Indiana glass factory in around 1908.

|

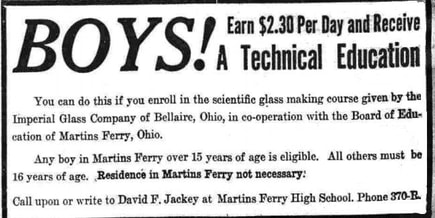

Below on the left is a 1919 ad for boys aged 15 and over, to work at Imperial. Interestingly, the ad was placed in a Martins Ferry newspaper and specifically aimed at boys from that area. Martins Ferry was the original home of Fenton before they established and moved to the Williamstown factory in 1906-7, and as the Imperial ad was specifically "in co-operation with the Board of Education of Martins Ferry, one could assume that there was a surplus of labour in that area. The attraction for working at Imperial - in Bellaire some 8 miles away - would have been the promise of a "Technical Education". We also know that some glass factories provided lodgings for their workers.

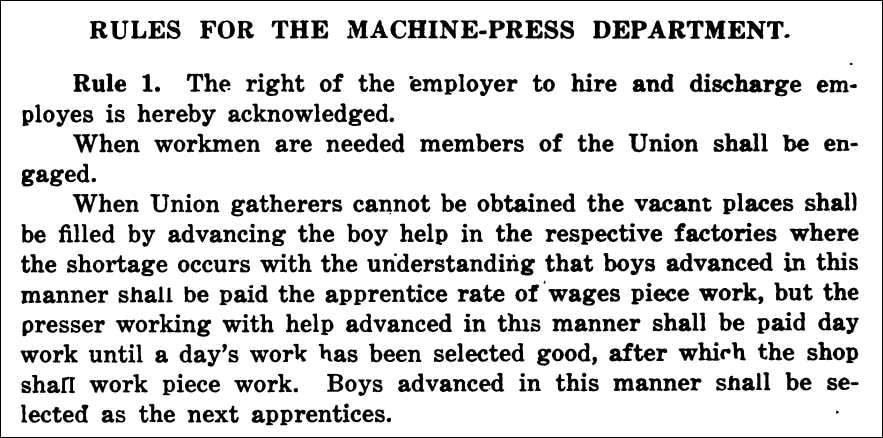

On the right is another extract from an AFGWU agreement, which gives us an insight into how boys could advance themselves into apprentice roles, and better rates of pay. The rules also acknowledged that using the lesser skilled boys-apprentices could affect the day's output: in this case, the skilled presser was to be paid for a full day's output, whether achieved or not, and that any additional output was to be paid on the agreed piece work basis.

Below on the left is a 1919 ad for boys aged 15 and over, to work at Imperial. Interestingly, the ad was placed in a Martins Ferry newspaper and specifically aimed at boys from that area. Martins Ferry was the original home of Fenton before they established and moved to the Williamstown factory in 1906-7, and as the Imperial ad was specifically "in co-operation with the Board of Education of Martins Ferry, one could assume that there was a surplus of labour in that area. The attraction for working at Imperial - in Bellaire some 8 miles away - would have been the promise of a "Technical Education". We also know that some glass factories provided lodgings for their workers.

On the right is another extract from an AFGWU agreement, which gives us an insight into how boys could advance themselves into apprentice roles, and better rates of pay. The rules also acknowledged that using the lesser skilled boys-apprentices could affect the day's output: in this case, the skilled presser was to be paid for a full day's output, whether achieved or not, and that any additional output was to be paid on the agreed piece work basis.

Naturally, working conditions varied from one factory to another, but two features were prevalent on the factory floor everywhere - heat, and dust.

Investigators for the US Commissioners of Labor found that the average indoor temperature on the factory floor over the year varied between 100 and 130 degrees F (38 to 54 degrees C). On one day when the outside temperature was 90 degrees F (32 degrees C), the following indoor temperatures were

Investigators for the US Commissioners of Labor found that the average indoor temperature on the factory floor over the year varied between 100 and 130 degrees F (38 to 54 degrees C). On one day when the outside temperature was 90 degrees F (32 degrees C), the following indoor temperatures were

|

recorded: at the glory hole 118 degrees F (48 degrees C), mould-boy's station 113 degrees F (45 degrees C), and at the snapping-up position 103 degrees F (39 degrees C). Generally, the glass factories shut down during July and August due to the heat. In addition to the heat, another factor having deleterious effects on nearly all glass factory employees was the heavy dust content of the air.

It is therefore not surprising to find the Union rule shown on the right! |