Companhia Fábrica de Vidros e Crystaes do Brasil

Glass and Crystal Company of Brazil

“ESBERARD”

By Claudio Deveikis

“ESBERARD”

By Claudio Deveikis

Translation and enhancement of archive images by Glen and Stephen Thistlewood

XIX Century (19th Century)

|

In 1838, Antonio Francisco Maria Esberard, the founder of the Glass and Crystal Company of Brazil [Footnote 1], arrived in Brazil as a baby, together with his family. His father, Fernando Bernado Esberard, (born in Marseilles, France) purchased a plot of land in Vila Inhomirim, about 30 miles away from Rio de Janeiro, in the area currently known as Magé, and established a small pottery works there.

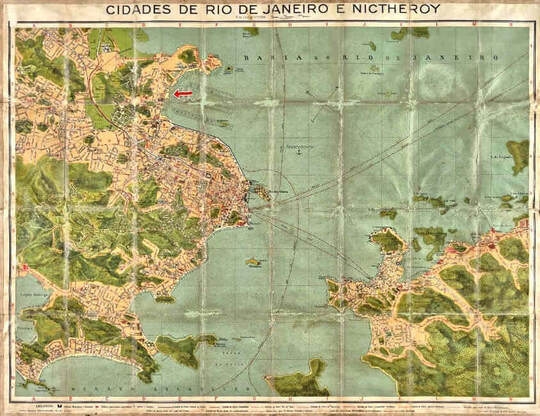

The business was not to last: after Fernando contracted malaria and two of his friends died from it, he decided to leave Inhomirim and move to the city of Rio de Janeiro, where he established another ceramic factory in the São Cristóvão neighbourhood, on General Bruce Street. Above: detail map of the São Cristóvão neighbourhood.

The red arrow points to the Esberard factory, “Fabr. de Vidros", on General Bruce Street, and Esberard's dock on the beach. |

Above: a 1914 map of the cities of Rio de Janeiro and Nictheroy, separated by the stretch of water known as Guanabara Bay. The red arrow indicates the general location of the factory near São Cristóvão beach. Sand used for glassmaking at Esberard came from Niterói (the present day name for Nictheroy).

|

|

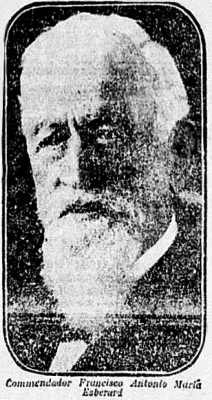

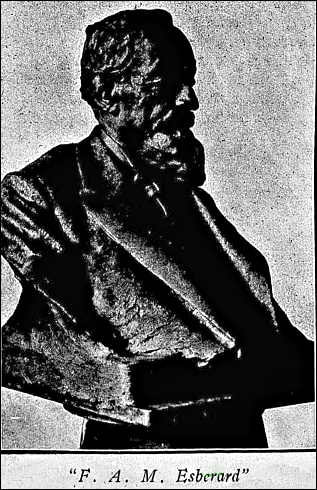

Fast forward to 1882, and after the death of Fernando Bernado Esberard, the ceramic factory was taken over by Antonio F.M. Esberard, who also acquired a small glass works in Saco do Alferes (a small cove that is no longer shown on today’s maps). Just twelve workers were employed there. Two years later, in 1884, and with a capital of 1 million Brazilian Réis (today, R$ 50,000 or approx. US$ 12,007) [Footnote 2] Antonio F.M. Esberard established the Companhia Fábrica de Vidros e Crystaes do Brasil (the Glass and Crystal Company of Brazil) on a plot in front of his father’s factory. At its founding, Esberard had a small furnace and thirty workers, and was producing low-cost, household articles. At this time, Brazil was an empire (1822 to 1889) and in the 1880s, Antonio F.M. Esberard had received the Commendation of the Rose, which had been conferred on him by the Brazilian Emperor, D. Pedro II. Following that award, Antonio was known as Commander Francisco Antonio Maria Esberard (pictured, right in 1922). In 1890, with an increased capital of 400 million Brazilian Réis (today, R$ 20,000,000, or approx. US$ 4,802,613), and with the land where the factory was situated being leased to the navy, the Esberard business was incorporated. 1900 to 1930

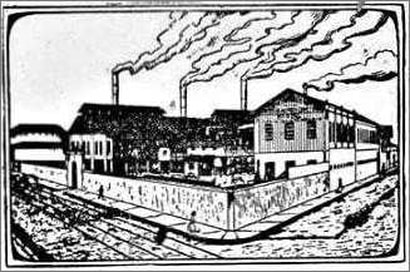

The main part of the factory – the glass and crystal section – was located at 1, General Bruce Street, Rio de Janeiro.

|

Above: Commander Francisco Antonio Maria Esberard, from "A Noite" 31st January 1922.

Below: in the early 1920s there was a bust of Commander Antonio F.M. Esberard in the courtyard. It had been sculpted by the Portuguese artist, Rodolpho Pinto do Couto. Sadly, this was lost in the great fire of 1925. |

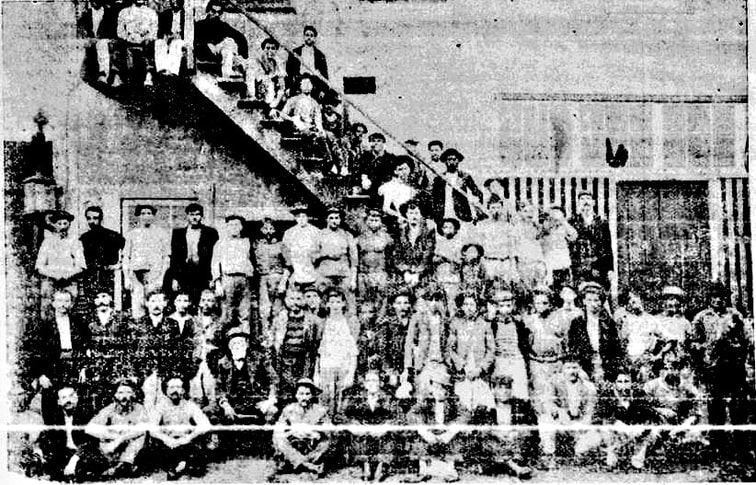

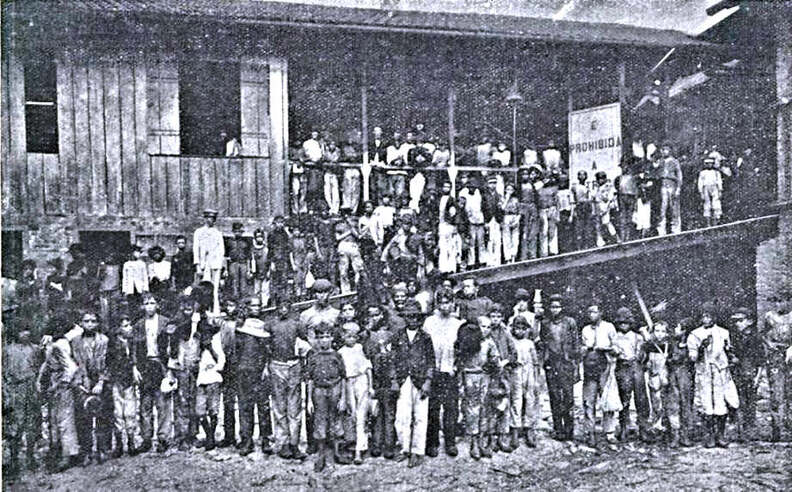

The following three amazing images of Esberard's workforce appeared in the “A Imprensa” newspaper of August, 11th, 1908. The original images were all extremely low resolution, blurred and difficult to see, but digital enhancement has improved them immensely. They are by no means perfect, but they give us a really important perspective of the people who were employed by Esberard at that time. |

Above: the man seated on the chair (front, left of centre) is in fact Commander A.F.M. Esberard.

In the central section of the buildings were the stables and an area reserved for the workers’ music band – the “Esberard Factory Band” – to rehearse in. The band performed at city events such as philanthropic (charity) functions and parties, inaugurations, celebrations etc.

|

Above: a small selection of the medals and awards won by the Esberard factory. Source: “A Imprensa” newspaper, August, 11th, 1908.

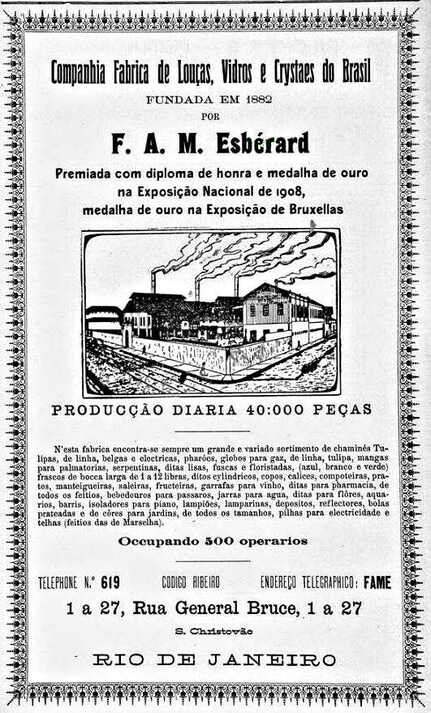

Esberard placed several ads in the press to promote its business abd its International success. On the right is an ad from 1910 that appeared in the "Almanak Laemmert". There is reference to the medals and diplomas that they had been awarded, and in fact there were many of them: Esberard’s glass received awards in several countries (see above). They included a bronze medal at the Paris Exhibition of 1889, a silver medal at the Saint Louis Exposition and Chicago Exposition in 1900, a silver medal at the Buenos Aires Exposition, a gold medal at the Brussels and Turin exhibitions and a gold medal at the National Exhibition that took place in Rio de Janeiro in 1908. Esberard’s glass works even received visits from dignitaries, including one in 1909 from the President of the Republic of Brazil, Nilo Peçanha. |

On the other side of the glass works, on São Cristovão Street, in the section facing the beach, there was a two-storey building that occupied around ten-thousand square metres. The ground floor was used to store crucibles, firewood, charcoal and crockery, while the upper floor was used as a staff dormitory and also housed a school for 150 students (comprising staff under the age of 18).

|

On the beach, a pier called Trapiche Esberard, was used to moor the factory’s speedboat that transported the sand for glass-making, from the city of Niterói, across Guanabara Bay to the glass works.

Commander Antonio F.M. Esberard’s residence was on General Bruce Street, opposite the factory. His wife was called Amelia and he had three sons (Alfredo, João and Etienne) and three daughters (Corina, Margarida and Elisa). Esberard’s sons all worked in the factory: Alfredo was the technical director, João was the commercial manager and Etienne was responsible for the accounting area. The 1920s brought tragedy and was marked by the deaths of both the Commander and his son, Alfredo, as well as a great fire in 1925. At dawn, on 30th January, 1922, Alfredo Esberard died. The following day, unable to bear the death of his son, Commander Antonio Francisco Maria Esberard passed away, at 2.30 in the afternoon The glass works had suffered fires before (in May 1912 and December 1913) but they were nothing in comparison with the terrible fire in July 1925, suspected to have been arson, that destroyed much of the factory. Amazingly, one exception to the damage was the production section, which was able to resume operations within a month of the fire. According to the newspaper “A Noite” (August 28th, 1925), the insurance company Sagres indemnified the company in the sum of Réis 457,380,000 (R$ 11,434,700; approx. US$ 2,745,822). |

The aftermath of the fire in May 1913.

Source “Revista da Semana” magazine. |

1930 to 1960

The name “Esberard Glass Factory and Crystal Company of Brazil” began to be used in the early 1930s, although the name “Esberard & Filhos (Esberard & Sons) Glass Factory” had been used in 1919 in two journals, “O Jornal” and “Jornal do Comércio”. It is most likely that – up to 1930 – the glass produced in the factory was not marked, and the moulded mark “Esberard Rio” began to appear from 1930 onwards. It is important to note that no records have actually been found to indicate that the company was known by the name “Esberard Rio”.

In the 1989 book “O Vidro no Brasil” (The Glass in Brazil) sponsored by the Sao Paulo and Rio Industrial Company, Cisper, the authors say, "A large fire completely destroys Esberard's facilities and marks the beginning of the end of the company's activities". The book also states that Commander Antonio Maria Francisco Esberard "died in 1916 and the factory continued to produce under the direction of his son Etiene Parisout Esberard until 1940, when it ended its activities."

This is not quite what the contemporary newspapers and magazines of the time indicate!

As has been stated above, Commander Antonio Maria Francisco Esberard passed away in 1922, not in 1916. After his death, João Esberard took over as Managing Director (he had been in office for a few years because of his advanced age). Etienne Esberard (the name Parisot, not Parisout, was the surname of Etienne's wife, and was not his name) appeared as Director of the Company from the early 1930s until 1946, the year he retired. Raul de Mello Rego signed the company's Accounts, as Managing Director, from 1947.

The name “Esberard Glass Factory and Crystal Company of Brazil” began to be used in the early 1930s, although the name “Esberard & Filhos (Esberard & Sons) Glass Factory” had been used in 1919 in two journals, “O Jornal” and “Jornal do Comércio”. It is most likely that – up to 1930 – the glass produced in the factory was not marked, and the moulded mark “Esberard Rio” began to appear from 1930 onwards. It is important to note that no records have actually been found to indicate that the company was known by the name “Esberard Rio”.

In the 1989 book “O Vidro no Brasil” (The Glass in Brazil) sponsored by the Sao Paulo and Rio Industrial Company, Cisper, the authors say, "A large fire completely destroys Esberard's facilities and marks the beginning of the end of the company's activities". The book also states that Commander Antonio Maria Francisco Esberard "died in 1916 and the factory continued to produce under the direction of his son Etiene Parisout Esberard until 1940, when it ended its activities."

This is not quite what the contemporary newspapers and magazines of the time indicate!

As has been stated above, Commander Antonio Maria Francisco Esberard passed away in 1922, not in 1916. After his death, João Esberard took over as Managing Director (he had been in office for a few years because of his advanced age). Etienne Esberard (the name Parisot, not Parisout, was the surname of Etienne's wife, and was not his name) appeared as Director of the Company from the early 1930s until 1946, the year he retired. Raul de Mello Rego signed the company's Accounts, as Managing Director, from 1947.

|

Raul de Mello Rego, as well as Managing Director of the Esberard Glass and Crystal Company of Brazil, had interests in other companies, among them Companhia Brasileira de Construcoes e Comercio, Braco, S/A ; Scientific ampoules and apparatus factory (Fabrica de ampolas e aparelho scientifico de M. M. Gomes & Cia Ltda.); Industrias Reunidas Mauá S/A; and National Explosives Safety Company (Companhia Nacional de Explosivos de Seguranca). In the Carioca Diary (Diario Carioca) of 1952, Raul de Mello Rego appears as employer President of the Rio de Janeiro Glass, Crystal and Mirror Industries Union.

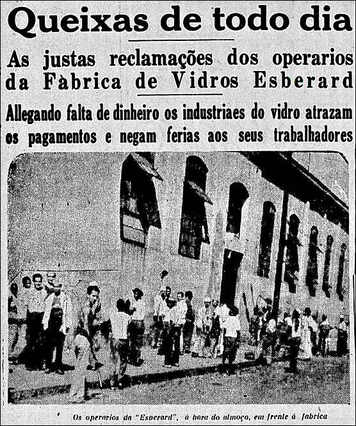

The 1989 book “O Vidro no Brasil” (The Glass in Brazil) also cites a great fire. It has been reported that the great factory fire occurred in 1925. In the 1940s, the only fire in the Esberard glass works was on 7th September, 1946 – and according to the newspaper “Diário de Notícias” of the same year, it was “a small fire without major damage”. From the 1930s, the Esberard company began to experience various difficulties, which gradually contributed to its eventual bankruptcy. There were numerous labour lawsuits due to delay or non-payment of wages, vacations and contract terminations. The newspaper report on the right was headed "Complaints Every Day" and stated the Esberard workers had "just complaints" alleging low wages in the glass industry and the denial of holidays for the workers. Furthermore, fines were paid to health authorities, municipalities and other agencies, for a variety of reasons including delay (or evasion) of taxes, unlicensed building, improper use of sand-washing land, and child labour terms (keeping children under the age of 18 working more than six hours a day). Due to high government tax rates, the company also suffered a loss of orders for its products. One pharmaceutical company cancelled the order for 160,000 jars for its “Bright Lotion” and 60,000 jars for its “Rugol Cream”. In the 1940s, it was apparent that the Esberard company took steps to rescue its image and reverse the crisis situation that it was clearly in. The “Jornal dos Sports” of the 19th October, 1943 carried an announcement stating that the company was hiring apprentices aged 14 to 17, and would pay, in addition to the salary, a bonus of Cr$ 30 (R$ 300, approx US$ 72) to those who worked for a full twenty-five days of the month. |

A June 1935 newspaper report showed discontented employees in front of the Esberard factory.

Source: "A Manhã" 30th. June 1935. |

In another promotional move, from 1945 to 1946, lunches and parties were offered to the employees to celebrate the company’s Jubilee. According to the “Tribuna Popular” newspaper of February 3rd, 1946, it was “another high example of worker-employee co-operation”.

In “O Cruzeiro” magazine, 1st September, 1945, a report noted that, despite the war, the Esberard factory was investing in new machines and facilities, and photos were shown of the new warehouses that were being built to replace the old ones. There were also photos of the interior of the factory were it was possible to see new machinery and furnaces.

The 1950s started with a call by the company’s shareholders (1st May, 1950) for an extraordinary general meeting, where they would deliberate on a loan with Banco do Brasil, guaranteeing the company’s real estate. The loan was Cr$ 3,000,000 (R$ 18,750,000, approx. US$ 4,502,450). The approval by the shareholder’s was unanimous. In the same year, on 15th April, there had been a strike of 800 factory workers over the 25% reduction on their salaries as well as a lack of salary payment in March.

In “O Cruzeiro” magazine, 1st September, 1945, a report noted that, despite the war, the Esberard factory was investing in new machines and facilities, and photos were shown of the new warehouses that were being built to replace the old ones. There were also photos of the interior of the factory were it was possible to see new machinery and furnaces.

The 1950s started with a call by the company’s shareholders (1st May, 1950) for an extraordinary general meeting, where they would deliberate on a loan with Banco do Brasil, guaranteeing the company’s real estate. The loan was Cr$ 3,000,000 (R$ 18,750,000, approx. US$ 4,502,450). The approval by the shareholder’s was unanimous. In the same year, on 15th April, there had been a strike of 800 factory workers over the 25% reduction on their salaries as well as a lack of salary payment in March.

|

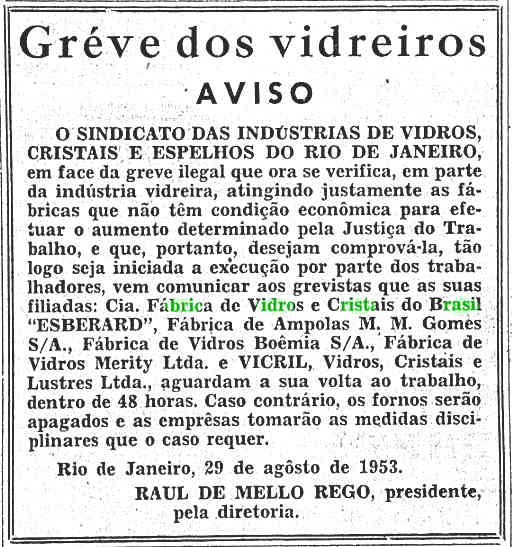

In December, 1952, there were two requests from the shareholders, the first of which was to approve an increase in capital for the company. The second request was published in the December 29th “Jornal do Comércio” in a piece entitled “How the Board was committed to transforming the production processes of the factory in order to meet the needs of the market, suggesting the sale of the real estate of the Régis de Oliveira 12th floor building, as well as the sale of the building of Rua General Bruce, corner of São Cristóvão beach ”. In reality – because of the large debts to the IAPI, the “Instituto de Aposentadorias e Pensoes dos Industriarios” (Institute for Industrial Retirement and Pensions) and to Banco do Brasil – Esberard was in danger of closing down. Because of this, on February 25th 1953, the then President of the Republic, Getúlio Vargas, intervened and instructed the President of the Banco Brasil (Anápio Gomes) to look into the matter. In August, 1953, the workers began what is generally considered to be the largest strike ever held at the Esberard factory. There were 120 days of shutdown, resulting in over 500 layoffs. On the right is a public warning issued by Raul de Mello Rego to the Glass, Crystal and Mirror Industry Union of Rio de Janeiro. It was issued on behalf of Esberard and its listed affiliate companies. Essentially the notice warned the Union that the companies could not economically afford a wage increase awarded by a Judicial Tribunal. It gave the striking workers 48 hours to return to work, otherwise the companies would take dismissal or disciplinary measures. At that point, it was impossible for Esberard to recover. There were numerous labour lawsuits and several other strikes, that continued through to 1956. In that year another shareholders’ meeting was held to resolve the sale of the company’s property at 55 General Bruce Street and São Cristóvão beach, because of the contraction of business activity. It was felt that Esberard would continue its activity in a more economical location. The latest information on the still-functioning Esberard Glass and Crystal Company of Brazil appeared in the “Jornal do Comércio” on 19th June, 1957, giving the Minutes of the General Meeting that had taken place on 14th June that year. |

A public warning from the then president of Esberard requiring that striking employees return to their duties.

Source: "Diário Carioca" 30th August 1953. |

Finally, in 1960, the only information that can be seen in journals is of sales announcements of the factory’s properties.

In PART TWO, I am showing a series of extracts from an Esberard catalogue, and

In PART THREE, there is a two page special feature showing some wonderful examples of Esberard's Carnival Glass.

* Footnotes:

The text of this Article was developed after research in the Hemeroteca da Bilioteca Nacional Digital.

[1] Brazil has undergone some orthographic (language conventions) reforms, detailed below:

The name “Company Glass Factory and Crystaes of Brazil” appears in records between 1890 and 1910 – after which, the name Brazil began to be written with a letter “s” – Brasil.

In the 1940s, Crystaes is now written Crystals.

In the text, the author decided to use the full title: Companhia Fábrica de Vidros e Crystaes do Brasil.

[2] The Brazilian currency has changed over time.

The "Reis" from the colonial period until 1942 and the "Cruzeiro" from 1942 to 1967 were used, a period near the end of the research. Currently, the Brazilian currency is the "Real".

In the research, it was decided to keep the value of the time with the following nomenclature: Réis, for Réis itself, Cr for Cruzeiro.

Following the original values, the updated values are shown in R $ (Real) and in US$ (United States Dollar).

For the conversion of epoch values to the current currency, Real, we used the Estadão Stock Values Converter, and the exchange rate used to convert Brazilian Real to US Dollar is the Central Bank of Brazil quote on 30th September 2019.

The text of this Article was developed after research in the Hemeroteca da Bilioteca Nacional Digital.

[1] Brazil has undergone some orthographic (language conventions) reforms, detailed below:

The name “Company Glass Factory and Crystaes of Brazil” appears in records between 1890 and 1910 – after which, the name Brazil began to be written with a letter “s” – Brasil.

In the 1940s, Crystaes is now written Crystals.

In the text, the author decided to use the full title: Companhia Fábrica de Vidros e Crystaes do Brasil.

[2] The Brazilian currency has changed over time.

The "Reis" from the colonial period until 1942 and the "Cruzeiro" from 1942 to 1967 were used, a period near the end of the research. Currently, the Brazilian currency is the "Real".

In the research, it was decided to keep the value of the time with the following nomenclature: Réis, for Réis itself, Cr for Cruzeiro.

Following the original values, the updated values are shown in R $ (Real) and in US$ (United States Dollar).

For the conversion of epoch values to the current currency, Real, we used the Estadão Stock Values Converter, and the exchange rate used to convert Brazilian Real to US Dollar is the Central Bank of Brazil quote on 30th September 2019.